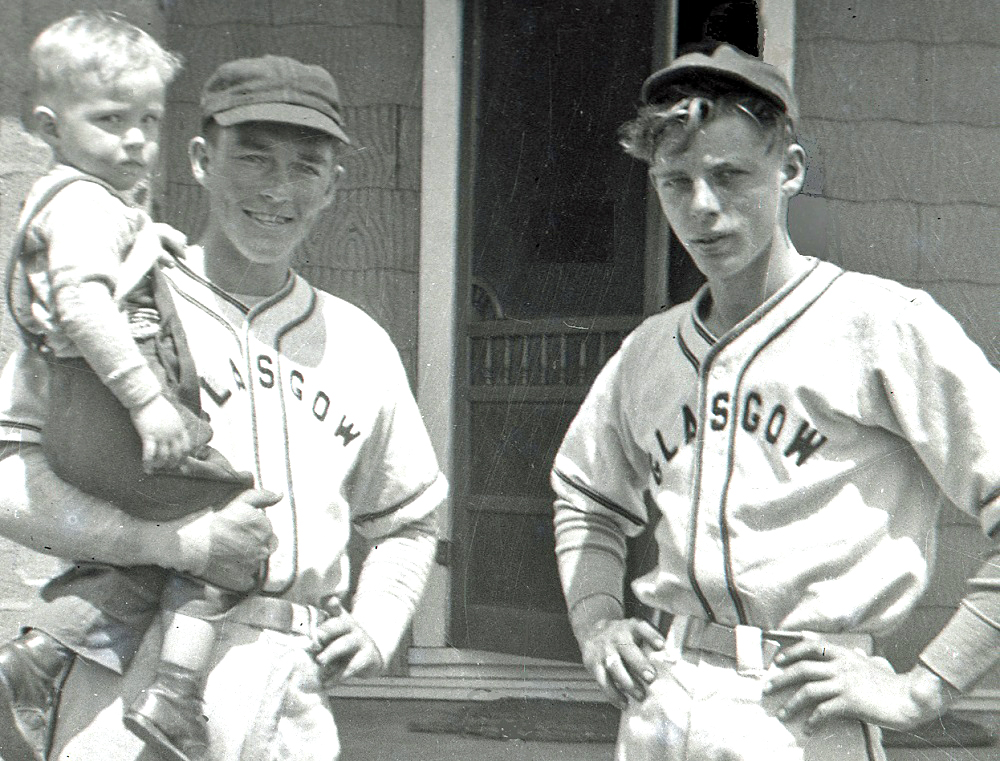

The photo is of Gene and Jim horsing around at our hotel in Sarasota, April 2009.

|

A reunion in old age

In April of 2009, our sister Dolores in Sarasota was ill. She asked that her three surviving brothers come visit her. Jim and Gene were both mid-eighties by then, but they said yes, they would fly from Kansas City to Tampa. I said I would fly there from Toronto and meet them on arrival, then drive the three of us to Sarasota.

As our reunion approached, I got to worrying about too much togetherness. The thought of Jim and Gene sitting next to each other for two and a half hours on the plane weighed on me. They might not be on speaking terms by the time the plane landed. A further hour and a half together in the car to Sarasota might be misery for all three of us.

I therefore made a mental list of questions I could ask in the car about life on the farm before I was born. This was something I had genuine interest in, something they both knew lots about. If I could keep them talking about old times, we might make the drive without a fight.

Luckily, Southwest Airlines does not permit seat selection in advance, and Jim and Gene could not sit together on the plane. On the drive to Sarasota, Jim sat beside me in the front seat, Gene in the back. I pulled out my old-times questions one after another. Conversation moved along happily.

Then, in answer to one of my questions, Jim gave a long monologue, recounting endless fascinating details about something or other. When at last he finished, I waited for Gene to add his own details, but the silence from the back seat went on and on. At last Gene spoke.

“Jim, goddammit,” he said, “when you tell a story, it has to be true. You can’t just make things up.”

All three of us laughed. It was a replay of hundreds of earlier exchanges. Right brain versus left. Salesman versus engineer. All three of us laughed. It was a replay of hundreds of earlier exchanges. Right brain versus left. Salesman versus engineer.

As things turned out, for me and I think for all of us, the few days we spent together in Sarasota were a hallowed time. We three brothers shared a hotel suite. I was struck by Jim’s and Gene’s gentleness and patience toward each other, as also to Dolores and to me. We would never all be together again, though Jim would live almost ten years more, and Gene eleven. Now in 2020, only Dolores and I are left. |

All three of us laughed. It was a replay of hundreds of earlier exchanges. Right brain versus left. Salesman versus engineer.

All three of us laughed. It was a replay of hundreds of earlier exchanges. Right brain versus left. Salesman versus engineer.