How my old red hen with scaly legs helped Dad catch a thief

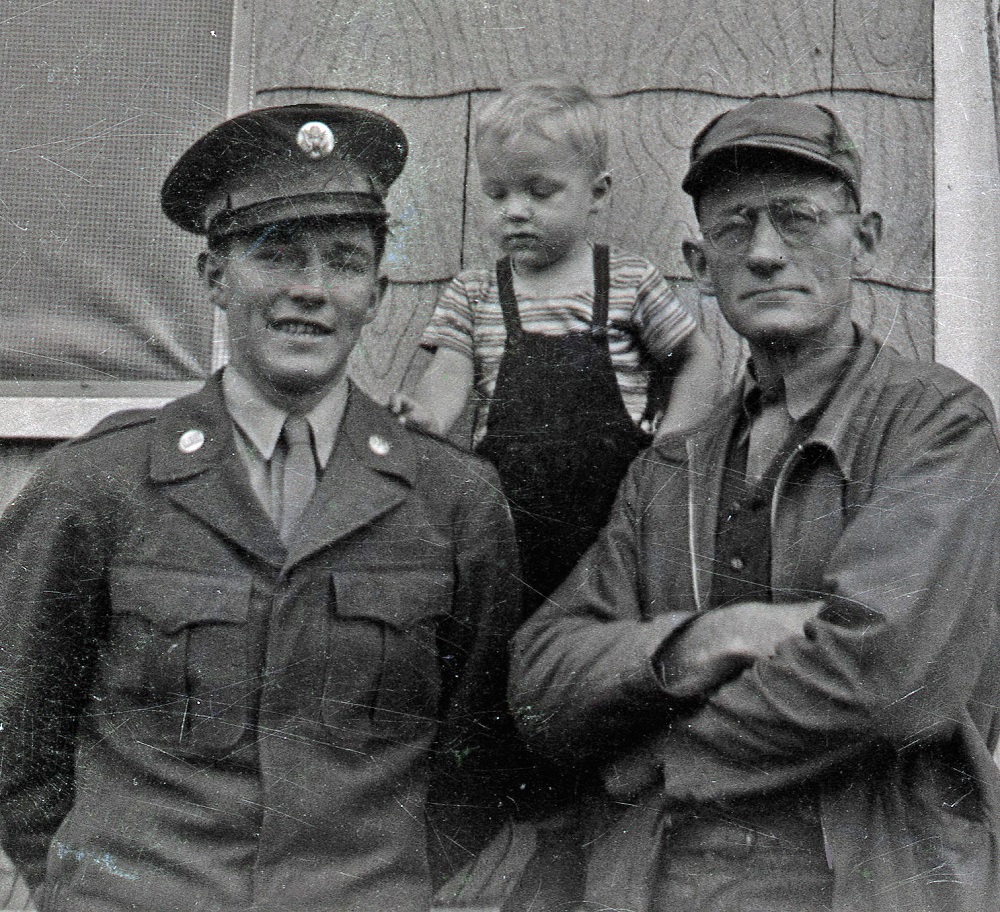

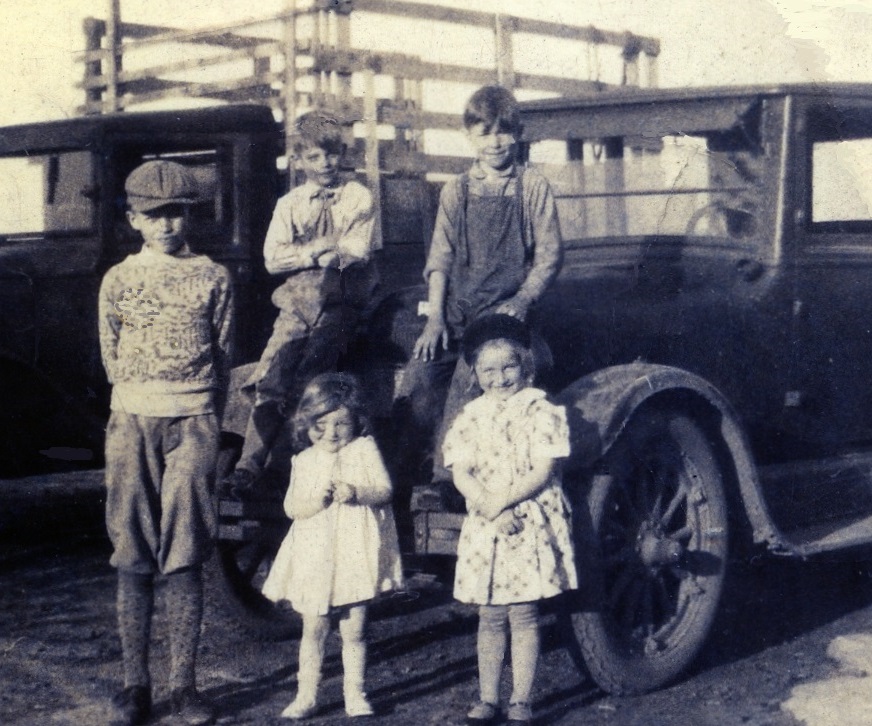

This story about how a crime was solved begins with the plain fact that Dad wanted to mold his sons into decent men, responsible workers, not sissies. He was a no-nonsense guy. In no way did he baby us boys. From little on, he got us to work.

Once, in the early thirties, when Bud, Gene, and I were all under nine years of age, he offered each of us a penny a row to hoe weeds out of corn. Jimson weeds, horsetail, pigweed and hemp could sap nutrients from the soil. Bindweed and morning glory could suffocate the young stalks of corn by twining around them.

Dad knew we would accept his challenge. The rows were about a hundred feet long in the field just west of our house, planted on contour from the creek on up to the top of the hill.

I worked my tail off for a week to make a hundred rows free of weeds. That made Dad smile. I always strived hard to please him, so I could see his pleasant side.

After he paid me the dollar for my work, I used it to negotiate with him the purchase of his big red chicken. This bird was in the flock of about a hundred hens that were kept in the basement barn just up from the pond in the pasture east of our house. The hens would graze a long distance from the barn toward the road, eating grass and grasshoppers and anything else digestible.

I had observed the flock when I was sent to feed them and gather eggs for Mother’s grocery money. I had noticed the big red hen. She stood out, because most of the hens were white. More than that, she was the boss, top in the pecking order. I wanted to own the boss.

Years passed. Dad would sell the older hens each year and replace them with pullets just coming into their prime. But I would not let Dad sell my old red hen, nor another gray hen that was even older. They showed their age, were in fact on their last legs, but I just could not let them go. Dad respected my wishes.

I think it was in 1937, when I was about thirteen years old and when the old red hen was about seven years old, that Dad noticed that his flock of a hundred hens was dwindling week by week. After a couple of months, the flock was down to a dozen white hens and my big red hen, the boss.

Then suddenly, the boss herself disappeared.

Dad had a suspicion of what was happening. On the other side of the road from the pasture where the hens grazed there lived a black couple, husband and wife, Henry and Odessa Miller. They were in their late twenties, both of them good-looking. They had a pretty baby girl who accidentally suffocated to death while sleeping in the bed with her parents. The wake for the baby was held at the farmhouse of our neighbors directly across the road, the Weber family.

Henry Miller was well-liked and a good worker. He hired out regularly to Dad and other farmers.

Dad said to him, “If I find the person stealing my chickens, I will blow his head off.”

Henry answered, “I wouldn’t blame you.”

Now Henry had a beautiful knife. Dad borrowed it from him, then happened to show it to another of our neighbors, Everett Flaspohler.

Everett recognized the knife as one that had been stolen in a break-in at his home. He asked where Dad got the knife. Dad said he borrowed it from Henry Miller. In this way Everett knew that it was Henry who had committed the break-in and stolen the knife.

Dad and I then went down to Lewis Mill looking for evidence about the apparent theft of our chickens. Lewis Mill was a hamlet on the Wabash Railroad in the Chariton bottomland just off Highway 5 north of Glasgow. The elevator there was a thriving business, and the handiest place around to sell chickens.

Sure enough, the man at Lewis Mill told us that Henry Miller had been selling chickens there. Dad described my distinctive old red hen with the scaly legs. Yes, the man said, Henry brought her here to sell.

The day came for the arrest. Constable Burgess and Everett Flaspohler both came to our house. Dad walked over to Henry Miller’s house and asked if he could again borrow his knife. Then came Everett and the constable.

Dad said to Everett,”Is this your knife?”

Everett said yes.

Henry Miller said, “My uncle gave it to me.”

Dad said, “Henry, we have got the evidence on you. I will tell you right now if you are a man and own up to everything, I will go to bat for you because you are a good worker. But if you lie, I will let them throw the book at you.”

Henry admitted everything and was sentenced to one year in jail.

We kept Henry Miller as a friend. He visited us after the year in lock-up. He was a quality man who just fell into temptation. He said the chickens were so easy to catch, that some of them, on their own, grazed their way over near his house. He promised he had learned his lesson, and I think he did.

I was happy we did not lose Henry as a friend. I really liked him and felt for him because his grandparents had been slaves and he himself had suffered a lot of prejudice. He taught me much about baseball. One Sunday, Dad was short a player on his team because of injury. He asked Henry to substitute at shortstop. Henry was the star of the team that day: getting hits, making sensational plays, and also stealing second.

I was proud of Dad for forgiving Henry’s transgression. Dad believed that "to err is human, to forgive divine."

Henry and Odessa moved to Salem, Missouri, for better opportunities. A few years later, the house they had lived in burned to the ground. |