|

|

How Grandpa and Grandma went bust

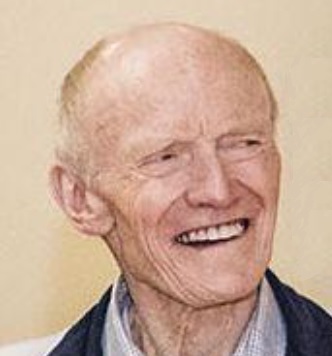

My mother and Grandpa himself told me a lot as a boy about his early life in Missouri, his marriage to Bertha Whitman, their move to Colorado, and their life on the plains, but nothing about Grandpa’s financial history. No mention of the moment of truth in 1935. The paragraphs below come from my piecing together, long after Grandpa and Grandma were gone, bits of information from my parents, older siblings, and public records.

The eight years on the prairie east of Colorado Springs, 1910 to 1918, failed in their main purpose, namely to cure Bertha of TB and restore her to health. Her death in 1915 left John with three young children but without their mother, the woman with whom, by all accounts, he had been head over heels in love. He and the children felt this loss for the rest of their lives.

Financially, however, the Colorado years were a success. The family arrived from Missouri with just enough money, maybe $1000, to buy a claim made a few years before under the Homestead Act. The family then lived on that quarter-section of land long enough and met all conditions required to “prove up” the claim and have clear title. I do not know how much Grandpa sold the homestead for in 1918, possibly as much as $10,000. It was enough that he could move back to Missouri with a car and with sufficient capital to buy land, machinery and livestock with which to resume farming.

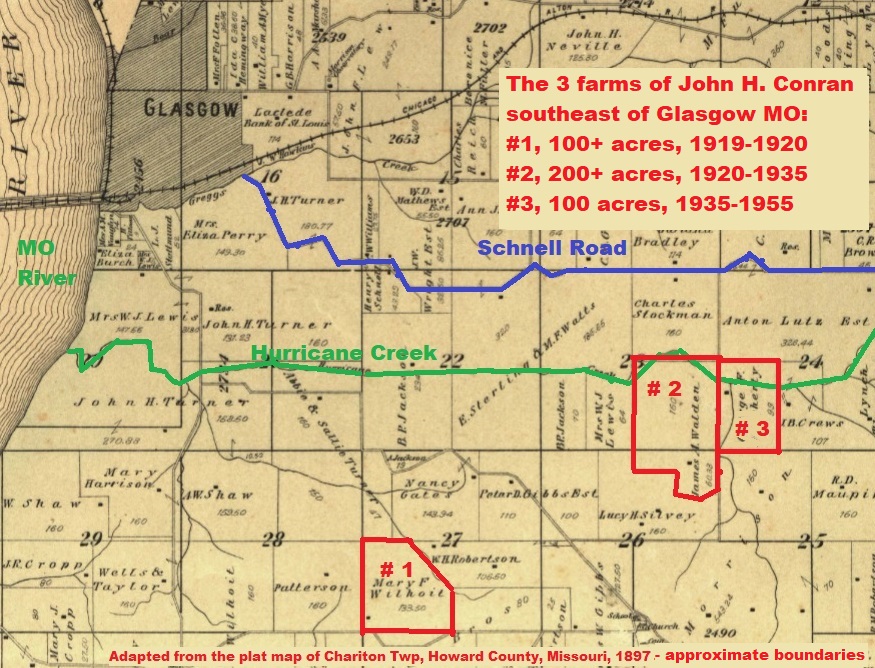

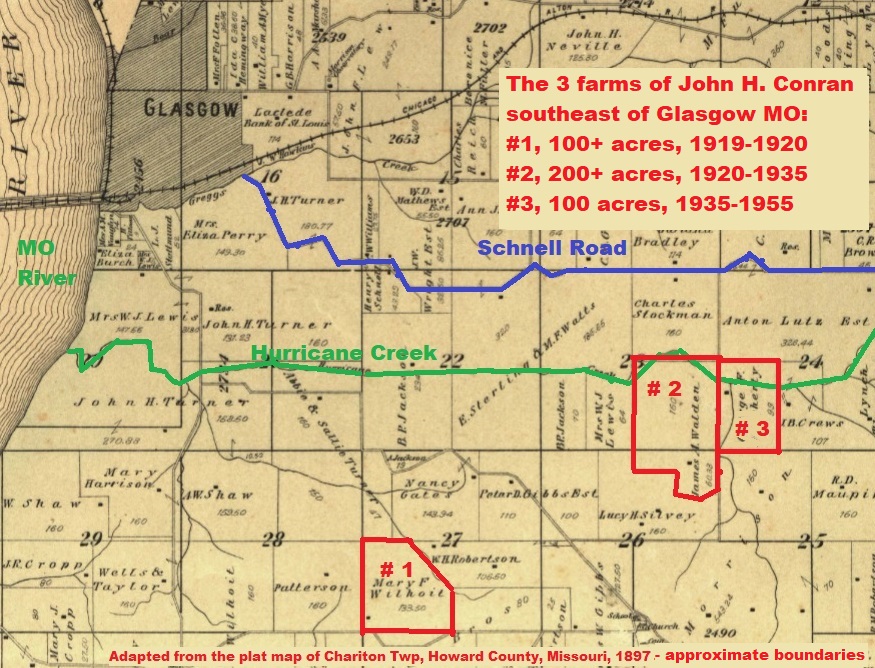

Having decided to make the Glasgow community home, Grandpa first bought the farm identified as No. 1 on the map below, in the southern watershed of the Hurricane Creek. This was in 1919. He sold that farm the next year. Mom said she never knew why. My guess is that, in the context of a booming economy and rising land prices, he seized a chance to make a profit, with the goal of buying a bigger, better farm.

In 1920, Grandpa bought what the map shows as Farm No. 2, in the watershed of the same creek. It had more than 200 acres, was mostly high ground, on a decent road, with a barn, outbuildings, and the commodious house pictured earlier in this essay. Almost certainly, this purchase required a hefty mortgage, but this would not have worried Grandpa. Farmland had risen in value pretty steadily throughout his 48 years. It seemed a safe investment.

This was the farm where John and Lena began their married life in 1921. I doubt that Lena brought much if any money to the marriage. She came from a relatively poor farm family. Her parents were immigrants from Baden, Germany. As her five siblings married and moved away, she had stayed home to help her parents. Then her mother died in 1912, at the age of 65. Lena stayed on after that, keeping house for her father, until she and Grandpa married.

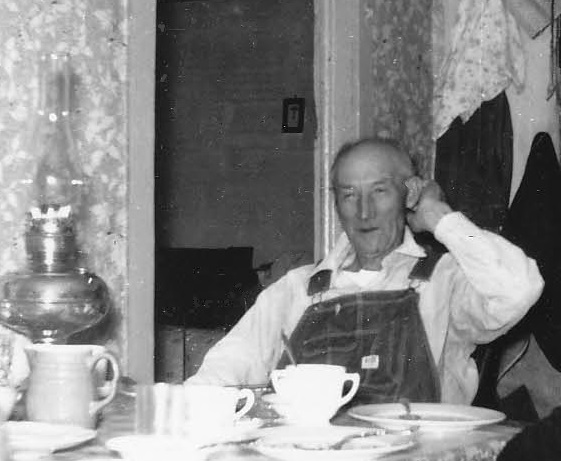

From 1921 to 1929, John and Lena lived frugally but well. Neither had expensive tastes. They both worked hard on the farm, tending the usual mix of horses or mules, cattle, hogs, turkeys, and chickens, as well as crops of corn, wheat and vegetables. Sometime in this period, they had a telephone installed. They may also have had electricity. It was a simple but more comfortable life than John had had on the Colorado homestead, probably also than Lena had had in her parents’ home.

Then Missouri’s agricultural economy collapsed, precipitated by the stock-market crash in October 1929. Prices plummeted for land and for just about everything farmers produced. To make matters worse, severe drought devastated crops, hayfields and pastureland in four of the next five years, especially in 1930 and 1934.

Generally, farmers who were debt-free and had money in the bank when the depression began survived it well enough. Some prospered. On the other hand, the hundreds of thousands who were deeply in debt faced ruin. John and Lena were in the latter category. They could not pay the interest on their mortgage, let alone pay down the principal, and the farm now was worth far less than they had paid for it.

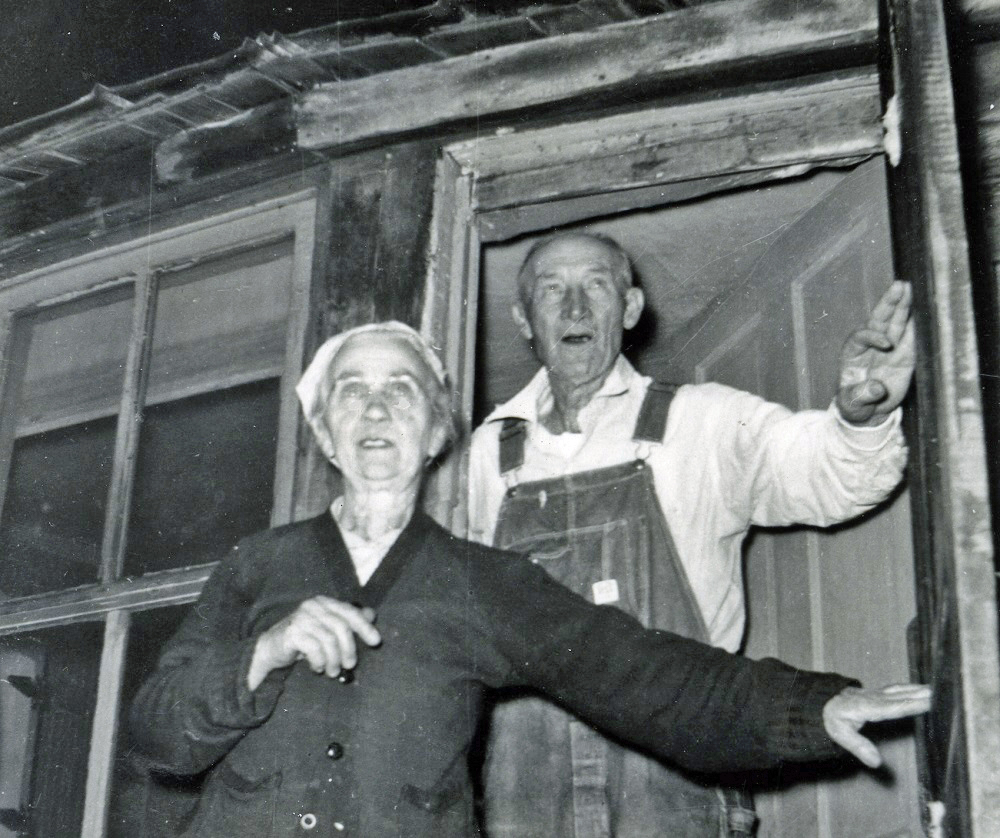

The long and short of it is they lost the farm. One day in 1935, a couple from Iowa arrived at John and Lena’s door, explaining that the mortgagee had repossessed the farm and advertised it for sale in a magazine, that they were the new owners and were there to take possession. John and Lena would either vacate the property voluntarily or be evicted.

This was the event that was never talked about as I was growing up. Undoubtedly, it was for Grandpa the worst thing that ever happened in his life, apart from Bertha’s death twenty years earlier. Mom told me decades later Grandpa had always said, given the longevity in his lineage, that he was going to live to be a hundred, but that after 1935, he never said that any more.

The new owners from Iowa were apparently not sticklers, because they were content to share the large farmhouse with John and Lena for several weeks, until the latter could find a place to move to.

Lena’s father, Joseph Oser, by then 84 years old, came to the rescue. He had money enough, probably about $2000, to buy what is shown on the map as Farm No. 3 – smaller than Farm No. 2, decrepit, overgrown, run down, but better than nothing. Grandpa Oser agreed to turn this farm over to John and Lena, provided they would care for him there for the rest of his life.

Such is the chain of events that led to my grandparents living where they did and as they did when I formed my bond with them during my first dozen years of life. Lena’s father died in 1938. After that, a landless bachelor named Otto Voss lived with John and Lena, did some farm work in return for room and board. He slept in a tiny pantry at the south end of the lean-to across the back of the house. Grandpa called it “Ot’s room.” |