Every child a source of pride

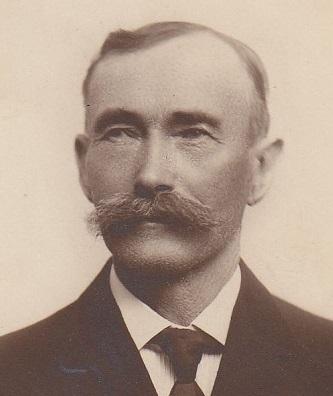

By the fall of 1921, at the age of 72, William was surrounded by proof of his success.

On the adjacent farm north of the homeplace lived eldest son Theodore with his wife Lena. They had lost their first two children in infancy, but now had three healthy boys: Ted, Norbert, and baby Raymond.

On the adjacent farm to the east lived the second son, William G., with his wife Emma. Already they had five children: Billy, Hank, Agnes, Edwin, and Joe.

On the adjacent farm to the northeast lived younger son Ben, who had married Viola two years before. Already they had daughter Berniece and a newborn named Walter.

William and Theresia’s oldest daughter Theresa had died of TB in 1916, but their two younger daughters were now married and living on farms nearby. Mary and Joe Flaspohler had a year-old daughter, Mary Teresa. Anna and Jule Oidtman were still newlyweds, having tied the knot the previous April; Anna was pregnant with a daughter they would name Freda.

Besides these five young farm families in Glasgow, there was son Henry’s young urban family in Jefferson City. Henry and Helen had two daughters, four-year-old Rosemary and a baby who would be called Bebe all her life. Henry had already made a name for himself as a lawyer, having been elected Prosecuting Attorney for Cole County in 1918, and re-elected in 1920.

One 37-year-old son remained unmarried but pleased his parents even more than those who had given them grandchildren. This was Joseph, ordained a priest in 1907. In September of 1921, just weeks before the fateful October 6, Father Joe had been in the news, appointed by Archbishop John Glennon to found a new parish in the St. Louis suburb of Riverview Garden, to be named for St. Catharine of Alexandria.

By 1921, only the two youngest sons were still with William and Theresia on the homeplace. John had celebrated his 26th birthday on October second. He and an Irish Catholic girl, Olive Conran, planned to be married the next spring. William intended to sell John the eastern half of the farm, a hundred acres on which he and Olive could build a new home.

The remaining hundred acres would stay with William and Theresia and their youngest son Fritz, the baby of the family, then 20 years old. Five sons on adjacent farms and two daughters nearby! This was beyond what the parents dared to imagine when they boarded the ship for America in 1892. |