This is the first of two essays I wrote for The Glasgow Missourian in observance of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Glasgow, which was fought on October 15, 1864. Click here for the second of the essays, "The Battle of Glasgow's Best Legacy."

Click here for the Wikipedia entry on the Battle of Glasgow.

The most authoritative accounts of the Battle of Glasgow are by historian James M. Denny: "Battle of Glasgow," Boone's Lick Heritage, Boonslick Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 3, September 1995, pp. 4-9; and a 25-page booklet with the same title, printed by the Blue & Grey Book Shoppe, 2001. So far as I can see, neither of these accounts is yet available online.

Click here for Lewis Library's page about the Battle of Glasgow, with numerous links and J. Y. Miller's splendid photo of Dunhaven as it looks today, the hilltop home of banker William Dunnica at the time of the battle. Confederate troops occupied the house during their attack, and fired from its windows at the Union lines. The latter fired back. The house is still pocked with bullet holes.

The Battle of Glasgow Was a Waste,

a

Small Victory on the Way to Defeat

Kenneth Westhues

|

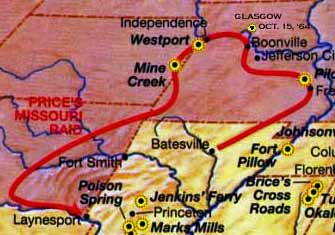

I have adapted the map at left from the National Park Service graphic of General Sterling Price's Missouri Campaign in the fall of 1864. The red line shows the route of his 12,000-man army, beginning near Batesville, Arkansas, proceeding toward St. Louis but swinging west after the Battle of Pilot Knob, then bypassing Jefferson City and heading north to Boonville. A yellow dot identifies Glasgow, where the battle was fought on October 15, en route to Price's defeat at Westport and his retreat southward through Kansas and south Missouri into present-day Oklahoma, what was then Indian territory. |

Article reprinted from The Glasgow Missourian, September 19, 2014.

Half a century ago, I was a 20-year-old farmboy from northeast of town with a fanatic interest in local history. As the centennial of the Battle of Glasgow approached, I wrote an account of it, which I then offered for publication in this newspaper.

Mrs. J. W. Stevenson, the great lady who was editor at that time, published it. The Moberly Monitor-Index reprinted it. I felt like I had won a Pulitzer Prize. It was an early milestone on my path through life as a teacher and writer.

For the present observance of the battle’s 150th anniversary, I considered writing an improved account, but thought better of it. Today, many people know far more than I about our town’s history during the Civil War. They include first-rate professional historians like Glasgow natives Lawrence Christensen and James Denny, and expert amateurs from both within and outside this community.

By now, moreover, relevant information and analysis are easily accessible to everyone online. Back in the 1960s, I had to borrow a key to the upper floor of Lewis Library from Miss Carrie Wachter, the very kind librarian, and then spend day after day poring over musty books and crumbling newspapers.

Today, anybody with a laptop or iPad can sit in an easy chair at home and call up thousands of relevant files. These include even primary sources about the war in mid-Missouri: newspapers, diaries, books, correspondence, photos, as well as official reports. The treasure trove of searchable files available is to the credit especially of the State Historical Society and the state government’s Missouri Digital Heritage.

The Essential Truth

There may nonetheless be some interest in the single main conclusion I have reached about the battle fought here, after reading and thinking about it off and on for decades in its larger context. It is a truth easily overlooked in study and re-enactment of the spectacle, the life-and-death drama of the battle itself.

The essential truth is that the Battle of Glasgow was a waste.

Confederate General Sterling Price was chiefly responsible for starting it. He hailed from Keytesville. He was a lawyer, plantation owner, slaveholder, and politician. He was Southern by birth, kinship, schooling, culture, and sympathy. He ranked at the top of the Little Dixie elite that controlled pre-war state politics, serving as Governor of Missouri from 1853 to 1857.

Price was also a military hero, having raised and commanded a regiment in the Mexican-American War and led it to an extraordinary victory in 1848.

By mid-1861, Price had decided Missouri belonged in the new nation formed in the South, the Confederate States of America. As he saw it, his job – first as commander of the State Guard, later as a CSA general – was to liberate Missouri militarily from Union control. In his view, the USA was a foreign occupying power.

Yet three years later, Confederate control of the state remained a pipedream. Union forces held St. Louis, most other cities, rivers and railroads. Bushwhackers, marauding bands of guerrillas nominally loyal to the CSA, terrorized and often murdered Union sympathizers, but Missouri as a whole was firmly lodged in the USA.

Price’s Campaign

Price had a grandiose plan for turning things around in early fall of 1864.

With delusions of impending glory, he led an army of more than 12,000 men north from Arkansas, intending to defeat Union troops in St. Louis, then proceed up the Missouri River to conquer the state’s heartland. Price brought with him the head of Missouri’s Confederate government-in-exile, Thomas Caute Reynolds, whom he intended to install as governor in Jefferson City.

Price never got to St. Louis. Eighty miles to the south, he lost a tenth of his army on September 27, in his attack on and capture of Fort Davidson near Pilot Knob. The Union garrison there was outnumbered six to one but suffered few casualties and escaped.

Deciding that an attack on heavily fortified St. Louis was too risky, Price turned his army westward, intending to take Jefferson City instead. But word came that it, too, was well protected by Union troops. Price hesitated to take them on. Skirting the state capital, he continued west, then veered north to Boonville, arriving there on October 11. He was now on friendly ground, Little Dixie. His troops celebrated by looting the town.

With St. Louis and Jefferson City beyond his ability to conquer, Glasgow became Price’s consolation prize. The Union storehouse here had weaponry and supplies worth fighting for, and the garrison consisted of just 800 men. Against them Price sent twice that number, commanded by Generals Jo Shelby (a wealthy plantation owner from Waverly) and John B. Clark, Jr. (a young lawyer from Fayette).

October 15, 1864

From the relative safety of the west bank of the river, Confederates began shelling Glasgow at 5:00 AM on Saturday, October 15. Their cannons were not precision instruments. Shot peppered homes all over town. Civilians huddled in basements or fled to the countryside.

The bombardment continued all morning. Meanwhile, CSA infantry and cavalry swarmed into town from the south and east, attacking the main body of Union troops dug in on Hereford Hill, where St. Mary’s Church and rectory are now.

At 1:30 PM, Colonel Chester Harding, commander of the Union forces, surrendered.

Shelby and Clark were not just officers but gentlemen. They followed the rules of war between sovereign states. Clark was a Harvard graduate; so was Harding, his enemy. At least 600 Union soldiers were taken prisoner and marched to Boonville, but paroled, treated with courtesy, and protected from bushwhackers. J.Y. Miller nicely recounted the remarkable true story in The Missourian of September 12.

If the Battle of Glasgow had clinched the outcome of Price’s raid, this would have given historical significance to the loss of lives and property. But the battle did not clinch anything. It was not even a turning point. Glasgow was a small CSA victory along the way to defeat. A week later, Price went up against a Union force of more than 20,000 men in the Battle of Westport (in present-day Kansas City). He lost, and retreated back toward Arkansas, Union troops nipping at his heels.

Confederate Defeat

The Confederacy as a whole was teetering. Sherman’s March to the Sea was about to begin. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox was just six months away.

With the collapse of the CSA in the summer of 1865, Generals Price, Shelby, and some dozens of followers fled to Mexico, intending to establish a colony there. The project failed. Price returned to Missouri on January 11, 1867, after a six-day steamboat voyage up the Mississippi from New Orleans. He was broken financially, spiritually, and physically. He died in St. Louis that fall, at the age of 58.

As in warfare generally, confusion reigned in the Battle of Glasgow. Of the roughly one hundred deaths, how many were from friendly fire is not known. In one well-documented case, Confederate artillery killed a revered apologist for the Confederate cause. William Goff Caples was one of the most famous and fervent clerical defenders of slavery in Missouri. Abolitionism, as he saw it, was the work of the devil. Union authorities restricted his teaching for a while, but he was minister of the Methodist Church in Glasgow at the time of the battle. He emerged from hiding in the parsonage basement and walked out to the front porch just when a twelve-pound shell came hurtling up Market Street from General Shelby’s cannons across the river. Rev. Caples died of his wounds four days later, at the age of 45.

Aftermath of the Battle

In Glasgow, the waste of lives and property continued after the battle was done. Confederate forces occupied the town only a couple of days before leaving with their booty to join the rest of Price’s army at Marshall. This left the town under no effective governmental authority at all, neither Union nor Confederate. Law and order could not be enforced.

Not surprisingly, the two most notorious gangs of bushwhackers descended on the town. First came William Quantrill and his bandits, famous for having murdered 150 civilians in a raid on Lawrence, Kansas, the year before. Quantrill entered Glasgow on the night of October 17, kidnapped the banker William F. Dunnica at his home at Fifth and Howard Streets (called Dunhaven, it still stands), took him downtown to his bank, and forced him to hand over the contents of the safe.

Four days later, on October 21, William Anderson and his hellions invaded the palatial home, Glen Eden, of Benjamin W. Lewis just north of town. Lewis was not just the wealthiest man in Glasgow but also a fierce Union supporter who had freed his slaves two years earlier. Lewis loathed the bushwhackers, and had put a price on Anderson’s head. Now Anderson came for revenge. For hours he humiliated and tortured Lewis, threatened to kill him, eventually accepting a $5,000 ransom instead. Lewis never recovered from his injuries, and died at the age of 54.

Price was defeated at Westport on October 23. Anderson was killed near Richmond on October 26. But in Glasgow, there was yet more waste and violence.

On or about October 29, a detachment of pro-Union Missouri militia reoccupied the town. Now it was the Union’s turn to exact revenge, since unlike Benjamin Lewis, most white residents of the area had actively supported the CSA and welcomed Price’s raid. The militia executed at least a dozen Southern sympathizers, and burned their homes and businesses.

Summary

In sum, the Battle of Glasgow greatly worsened the waste, misery, and terror of the war years in this area, while having virtually no effect on Price’s campaign or the war as a whole.

Still, in human history, nothing is so bad that no good comes of it. In a follow-up essay to this one, I identify a precious legacy of the Battle of Glasgow, one that endures to this day.