Academic life as it was, is,

and ever shall be (sigh)

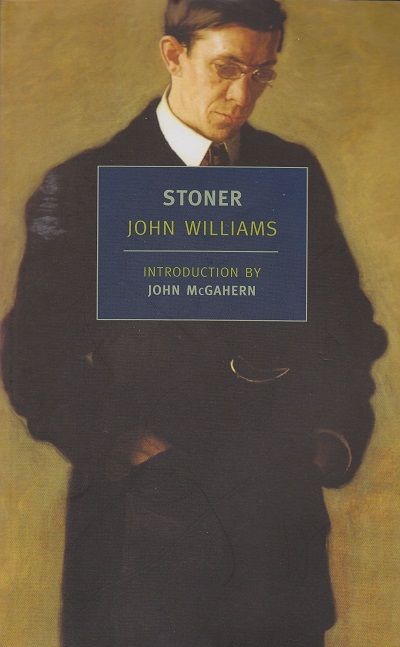

Review of John Williams, Stoner (Viking, 1965; Univ. of Arkansas, 1988; NYRB Classics, 2006).

Kenneth Westhues, University of Waterloo, 2012

In a 2011 email, Meira Weiss, an anthropologist-colleague in research on academic mobbing, asked my opinion of John Williams’s novel, Stoner. I had never heard of it. Turns out it was published to favourable review in 1965. It has nothing to do with drugs.

My respect for Weiss is such that I decided to read the book. The New York Review of Books has lately republished it. Finding a copy was not very hard.

The story of William Stoner is not a case study of mobbing in a university. It is bigger than that, sketching the English professor’s life from birth on a Missouri farm in 1891, to death 65 years later, shortly after honourable retirement from the University of Missouri with the title of emeritus.

Never during his long career is Stoner ganged up on by colleagues or administrators, never officially denounced, punished, humiliated, cut from the payroll or ousted from the faculty. The threat of being mobbed lurks for most of his career, on account of the enmity of his department chair. The two men do not speak for twenty years. Yet thanks to tenure, Stoner survives, having only to put up with being assigned odd classes in inconvenient time-slots.

The value of this book lies in its plain, clear, truthful, nonjudgmental depiction of the humanities side of campus in all its strange, quixotic dreariness. Even now, almost a century after the novel’s time frame, one can meet its characters along most academic corridors: Stoner himself, neither hero nor villain, soldiering on in his loveless marriage and lifeless specialty; Archer Sloane, Stoner’s mentor, who dies of heartbreak over World War I; Gordon Finch, Stoner’s dean, affable, astute, decent, aware of what a failure he would likely be in the outside world; Katherine Driscoll, Stoner’s lover and colleague, who dedicates a book to him long after they are through.

Williams offers his hardest insights into academic life through the voice of Stoner’s classmate in graduate school, David Masters, who is “too bright for the world” and won’t keep his “mouth shut about it.” Masters has a reputation for “arrogance and impertinence, and it was generally conceded that he would have some difficulty in finally obtaining his degree.” “We do no harm,” Masters opines, “we say what we want, and we get paid for it.” Williams spares readers the pain of observing Masters’s fate in the university, by having him killed in action at Chateau-Thierry.

Stoner, by contrast, accepts deferment from military service and continues work on his doctorate. In Williams’s telling, this decision on the one hand smacks of academic wimpishness and on the other hand reflects the wisdom of Archer Sloane: “You must remember what you are and what you have chosen to become, and the significance of what you are doing. There are wars and defeats and victories of the human race that are not military and that are not recorded in the annals of history.”

Stoner would be a fitting gift for any aspiring professor, or for any seasoned one, on account of the undistorted mirror it holds up to the academic enterprise. For the student of academic mobbing, its chief value is in dramatizing one common way in which this social process is prevented.

What turns Hollis Lomax into Stoner’s enemy is the latter’s refusal to give a passing grade to a lazy, incompetent fellow for whom Lomax has special fondness. The student gets his degree anyway, but Lomax harbors a grudge, deciding to bring formal charges of unethical behavior against Stoner, charges that could lead to Stoner’s dismissal. Lomax declares his plan in a meeting with Dean Finch at which Stoner is also present. Here is the beginning of what could become the full-blown mobbing of Stoner. As Finch remarks on a later occasion when Lomax might lead a mob, “If Lomax wants complainers, they’ll appear; if he wants witnesses, they will appear. He has quite a following, you know.”

Fortunately for Stoner, Finch nips the mobbing in the bud. He says to Lomax, “quietly, almost affably, ‘There will be no charges. I don’t know how this thing is going to resolve itself, and I don’t particularly care. But there will be no charges. We’re all going to walk out of here in a few minutes, and we’re going to try to forget most of what has been said this afternoon. Or at least we’re going to pretend to. I’m not going to have the department or the college dragged into a mess. There will be no charges. Because,’ he added pleasantly, ‘if there are, I promise you that I will do my damnedest to see that you are ruined. I will stop at nothing. I will use every ounce of influence I have; I will lie if necessary; I will frame you if I have to. I am now going to report to Dean Rutherford that the vote on Mr. Walker stands. If you still want to carry through on this, you can take it up with him, with the president, or with God. But this office is through with the matter. I want to hear no more about it.’”

Probably three-quarters of the academic mobbings I have studied over the past fifteen years, maybe more, would never have happened if some administrator in the relevant faculty had had guts enough to say something like what the fictional Dean Finch said.

One more thing I should say about John Williams’s magnificent book. I thought at first it would have special interest for me because, unusually, it is set in that part of the world where I was born and grew up. Stoner’s parents were poor farmers near the small town of Boonville. That’s about twenty miles from the hundred acres where I was raised. Stoner’s upbringing and mine were equally near the state university in a geographic sense, and equally far from it in a cultural sense. Having read many novels set in the large urban centres of the world, I did indeed find it fun to read one set in my own stomping ground, with occasional references to buildings and places I recognized from personal experience.

Yet by the time I finished this book, I was surprised by how little my enjoyment of it depended on its familiar setting. Academic life, as Williams describes it at the University of Missouri, differs in only trivial ways from what I have seen and been part of in many other cities, states and countries. What makes a great work of art is the deployment of particularities to capture general, even universal truths. Stoner is a case in point.