| K. Westhues homepage | Tributes directory |

Uncle Jim Conran's Legacy to Me

Kenneth Westhues, 2012

|

According to Frank Capra's 1946 classic, It's a Wonderful Life, people make more difference in others' lives than they generally know. My great-uncle Jim Conran is a case in point, at least in his effect on me.

I never met him. I was two years old when he died in 1946, at the age of 75. Whether anybody had let him know that his niece Olive Westhues had given birth to her sixth child, I don't know. I doubt it.

My mother spoke of Uncle Jim from time to time as I was growing up, always with fondness and respect but also with the taken-for-grantedness commonly accorded older relatives. Of course my grandfather had a brother one year older, of course he was a bachelor, and of course a lawyer in St. Louis who had earlier taught at Kemper Military School in Boonville. I heard nothing about his legal practice or politics. In the decades before my birth, I doubt that my parents had much contact with him. There might have been Christmas cards. He was just part of the woodwork of my ancestry.

All the same, Uncle Jim's being a lawyer was itself a big legacy to me. My father, both my grandfathers, all four of my great-grandfathers, and most of my uncles were farmers, men who did physical work for a meager living. I, on the other hand, was a bookish kid. I couldn't imagine my future behind a plow. That Uncle Jim had made his living in an intellectual way nourished my hope that I could do the same. He wasn't the only ancestor I modeled on. My father's brother Henry was also a lawyer, in fact a judge. Two of Dad's uncles and one of his brothers were priests. But Uncle Jim was the one ancestor on my mother's side who showed me a way out of rural life, an alternative to working mainly with my hands.

It did not bother me that his choice of a nonagricultural occupation was less than free. I'm not sure this fact even registered in my young mind. My older brothers have lately reminded me that Uncle Jim had a congenital deformity, probably clubfoot, used a cane throughout his life, and thus would not have made much of a farmer anyway. For me, what mattered was simply that he had made his life in the city, as what is called now a "knowledge worker."

Further, from my mother's passing references to Uncle Jim, I learned that he defied the rural stereotype of city folk as uncaring, uncompassionate. Mom's mother had died on their Colorado homestead in 1915, when Mom was thirteen years old. Three years later, Grandpa brought Mom and her two younger brothers back east and resettled the motherless family on a Missouri farm. At that point, 1918, Uncle Jim proposed to enroll my mother, then sixteen years old, in a finishing school in St. Louis. Her prospects would be better there, he said, than as a farmgirl in a rural community. His proposal came to nought. Grandpa said he wanted to keep the children together. Mom always said she was glad for that, but during the hardships of her life in subsequent decades, I'm sure she sometimes wistfully pondered what might have been.

|

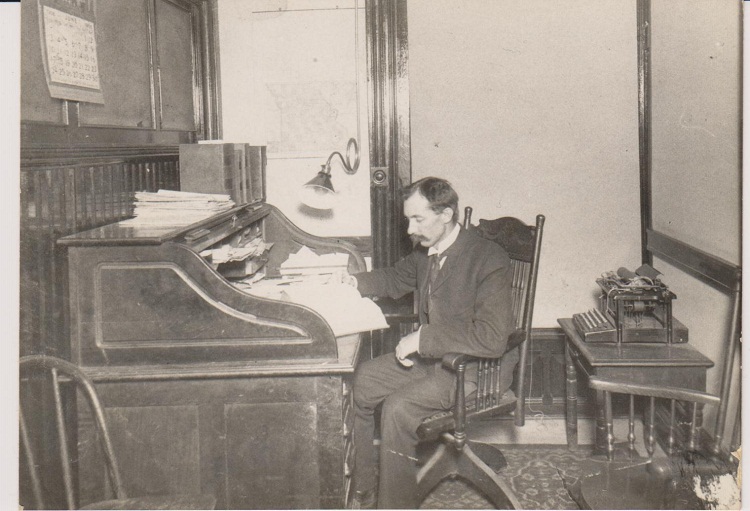

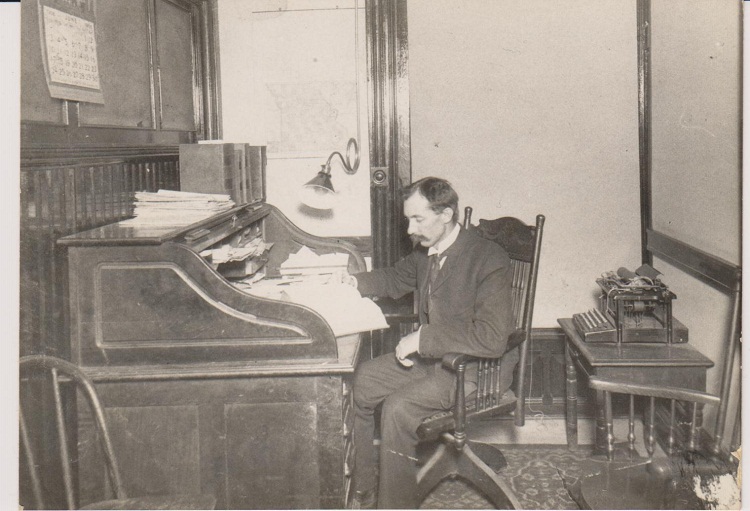

Lawyer James F. Conran stands with his father, the elder James Conran (1830-1922), who had immigrated with his mother from Ireland to the United States in 1850. The undated photo was taken probably about 1915. |

Uncle Jim apparently took no offense that Grandpa declined his offer to pay for young Olive's schooling. As things turned out, she dropped out after three years of high school in her rural community and got engaged to a German farmboy almost as poor as she, my father. They had a very small wedding in St. Louis in 1922. Uncle Jim provided a car and driver for the occasion, so that they could visit Shaw's Garden and other sights of the city that afternoon. For their wedding night, Uncle Jim arranged accommodation at the boarding house where he himself made his home.

That about sums up what I knew of Uncle Jim as I was growing up: that he was a kind man and a lawyer in the biggest city of the state. This information, however scant, was enough to nourish my hope of living my life beyond the confines of the rural community of my upbringing.

Uncle Jim was important in a further way, so I learned as a child. Because he had neither wife nor children, his property was divided on his death among his surviving siblings. In the early 1950s, I remember hearing Grandpa refer to "Jim's money." It was just two or three thousand dollars, maybe four, but for my grandpa and step-grandma, it made the difference between poverty and abject poverty in their old age. This was yet another act of kindness, a posthumous one, that Uncle Jim did for his rural kin.

Over the past few years, thanks to digital archives accessible online, I have learned a little of Uncle Jim's life as a young man. It turns out he was something of a leader of the student body at the University of Missouri, where he earned his law degree in the last years of the nineteenth century. Witness these items from The Independent, an antifraternity newspaper published by the student union:

December 7, 1895 — "J. F. Conran and W. W. Lewelling ate turkey with their best girls at Ashland."

September 26, 1896 — J. F. Conran, secretary of the Debating Club, planning a "literary organization of the university."

February 6, 1897 — Announcement of a debate between Missouri and Arkansas Universities on the question of whether railroads in the United States should be owned and operated by the central government. J. F. Conran was one of the three debaters on the Missouri side.

April 17, 1897 — In a debate on whether socialism should be substituted for the present industrial order, J. F. Conran argued the negative. "Old members say the discussion was the most animated one within the history of the club."

February 22, 1899 — J. F. Conran presided over the competition among eight contestants vying to represent Missouri University in an upcoming debate with the University of Kansas on whether the United States should adopt British colonial policy for her new acquisitions of Cuba, Porto Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines.

May 30, 1899 — Staff elect J. F. Conran editor in chief of The Independent for the upcoming academic year. "His long connection with the University and wide acquaintance with the students added to his literary training will render his election a fortunate one for the paper."

January 22, 1902 — News item that alumnus J. F. Conran is now practicing law in St. Louis.

From other newspaper archives and the annual Missouri Bluebooks available online, I have learned that Uncle Jim's politics (unlike in my father's family) were firmly on the left. He held numerous offices in local associations of the Democratic Party. An Illinois newspaper reported in 1913, that J. F. Conran had given a talk at a Catholic conference on "The Church and the Working Man."

Also in 1913, a Democratic governor appointed Uncle Jim to a three-year term on the seven-member State Board of Charities and Corrections, the body charged with overseeing the state penitentiary and institutions for war veterans, delinquent youth, the "feebleminded," the "insane", the blind, deaf and dumb, and so on. This appointment appears to have been renewed in 1916, for a further three-year term.

In 1915, according to the University Missourian, the governor appointed James F. Conran to the newly created, twenty-member Missouri Children's Code Commission. This body's mandate was to propose a "code of laws seeking to guarantee to every child in Missouri adequate protection, education, and opportunity." By 1918, the commission produced a 160-page report, "a complete revision of the laws for the welfare of Missouri children." Many of the commission's recommendations were passed into law, enlarging the state's acceptance of public responsibility for child welfare.

Control of the statehouse passed to the Republican Party in 1921. I can find no record of James F. Conran holding state office after that.

A search of St. Louis newspaper archives yields scant information about how Uncle Jim made his living, what kind of legal work he did. From this I conclude that he was a lawyer of little prominence, that the promise of distinction he showed in law school was not fulfilled in his later life. But that is neither here nor there.

The point of this memoir is that Uncle Jim had a big effect on me. From the front porch of the house where I was raised, family farms like ours stretched from horizon to horizon – in much the same way as many city kids today grow up seeing in all directions houses or townhouses much like their own. I desperately wanted to get beyond those horizons into some larger world. I wanted what had been beyond my parents’ reach: the chance to study, learn, read, reflect, write, answer questions, probe mysteries, travel across borders that my parents had had to stay within. By being who he was, Uncle Jim helped me do that.

By now the year is 2012. This undistinguished collateral ancestor of mine has been dead for 66 years. Whoever reads these lines can take them as corroboration of the point of Frank Capra's film. However little impact you think you are having on this world, it may well be that many decades after you are gone, somebody you never knew will write words of gratitude for you, words like mine for Uncle Jim.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Written on the basis of information from my late mother, Olive Conran Westhues, from my elder brothers Eugene and James, and from newspaper archives accessible in the Missouri Digital Heritage and in Chronicling America (Library of Congress).